The final day of the Arclight Symposium ended with a roundtable discussion on media history and digital methods. One suggestion emerging from this session was that we should share our research more widely, utilizing the platforms we frequently access, such as Twitter, Facebook, and Tumblr. This idea of using the everyday digital tools that surround us is also addressed in the article “Getting Started in the Digital Humanities,” posted on the Digital Scholarship in the Humanities website. This article advises to “follow & interact with DH folks on Twitter,” emphasizing how it can be an effective tool for creating networks and keeping up-to-date on research and events in this community.

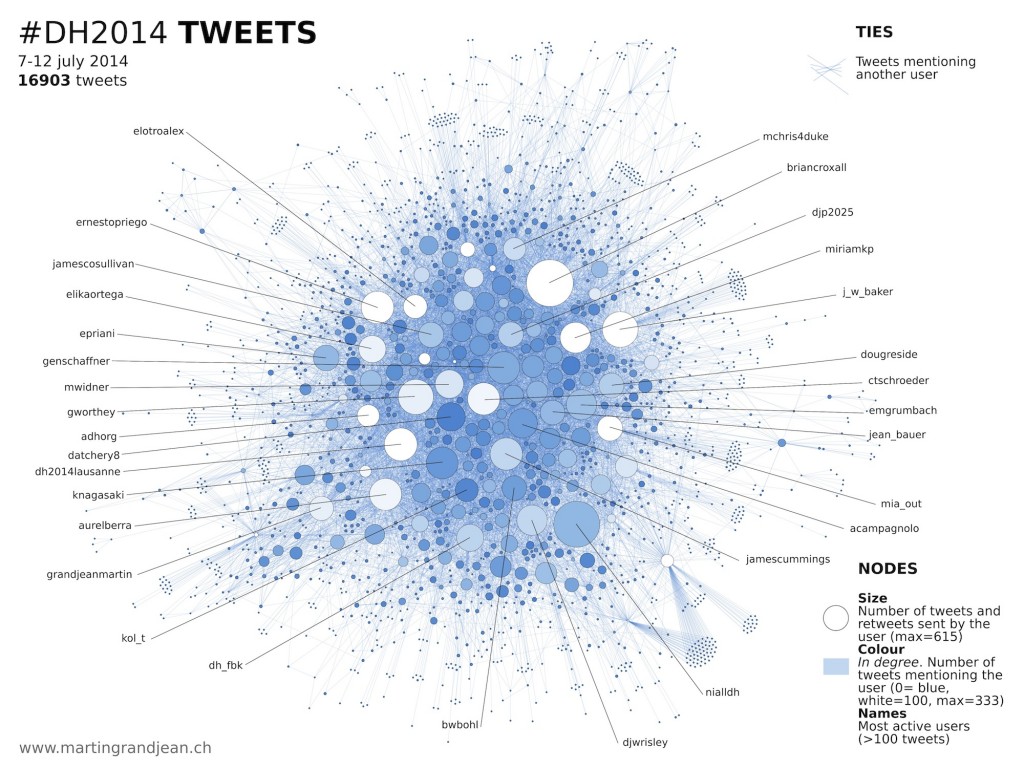

On his website Martin Grandjean notes the growing use of Twitter at digital humanities events, claiming that “the public of the lectures is at least as much present on Twitter than physically in the room.” Using the 2014 annual international conference of the Digital Humanities as an example, he reports that approximately 2,000 people posted around 16,000 tweets, while roughly 750 were actually in attendance. Grandjean and his colleague Yannick Rochat decided to turn the data from these tweets into some stunning visualizations.

In October 2014, Grandjean presented an article on the role of Twitter, entitled “Source Criticism in 140 Characters: Rewriting History on Social Networks,” at the International Federation for Public History Conference in Amsterdam. In April 2015, the first international and interdisciplinary conference on the use of Twitter for research was held in Lyon, France. The objective of this one-day conference was “to develop interdisciplinary awareness of the possibilities afforded by Twitter for research.” In addition to questioning how Twitter may be used for research, the conference studied Twitter “in its own right, with researchers testing whether traditional tools and theories still stand in the universe of 140 characters messages.”

Undertaking this practice myself, throughout the three days of the symposium I live-tweeted the panels, posting approximately 200 tweets to the @projarclight twitter account. Before the Arclight Symposium I did not use Twitter on a day-to-day basis and often struggled to find its use and place in my academic and personal life beyond retweeting an interesting link or something relevant to my research. However, my perception of Twitter changed when I experienced first-hand the process of live-tweeting an event.

Having never live-tweeted an event before, I quickly learned the value of Twitter in an event setting. Paying close and careful attention to the presentations, I summarized the presenters’ arguments in 140-character tweets. Not only did tweeting provide a useful tool for updating others who were not present, but it also facilitated discussion on Twitter. I became acutely aware of the latter as participants in the room were concurrently tweeting their own responses to the presentations, as conversations were developing, and as we started re-tweeting one another. This became another instance where the digital began to re-shape our experience, in turn creating an opportunity to consider how we can both utilize the digital and reflect on the impact the digital has on us.

In the months since the Arclight Symposium I have continued to employ live-tweeting as an important part of my academic conference involvement. I have discovered the ways in which live-tweeting has the ability to alter experiences of presence and participation in academic conference settings. To me, using Twitter is akin to adding an extra layer of conversation, contemplation, and circulation to my experience of listening to presenters describe their ideas and arguments; it turns active listening into a social experience. Rather than listening and making notes for my own personal use, I condense my notes into bite-size pieces of information to share on social media. As I mentioned earlier, Twitter not only enables individuals who are not at the event to get a glimpse of the emerging ideas and conversations, but it also has the potential to create conversations in its own right.

At the same time, we need to be critical and not simply celebrate Twitter for its capacity to reshape our experiences, the ways we share ideas, and how we document academic events. It is evident from Grandjean and Rochat’s visualizations that tweets produce more data, which we can analyze using a method of distant reading, but it is less clear beyond the additional data generated, what the value is exactly of each tweet. In live-tweeting the Arclight Symposium was I really adding more substance and meaning to the conversation, or was I simply adding more data, relaying ideas onto social media without contributing any analysis—analysis that Twitter and its 140-character limit essentially restricts. Although the entire structure of Twitter is based upon its short, limited posts, there are ways around its character-limit. For instance, individuals can post pictures that contain larger amounts of texts (yet, the process of live-tweeting is too instantaneous to allow the time for this), or connect multiple tweets together in a “tweetstorm” (Koh). Twitter however is beginning to recognize how its form may hinder meaningful discourse; for example, it is now considering an expansion of its character limit, perhaps by way of a paid option, with its recent announcement of “140 Plus” (Koh). To reinforce a point from my last article, with the growing use of Twitter among digital humanities scholars we need to contemplate what these instantaneous, short forms of writing might also mean for scholarship and the ways in which we reach audiences.

This discussion of Twitter invokes and thus provides me an opportunity to revisit and highlight some of the issues and topics that emerged at the Arclight Symposium, including:

- The vital importance of paying attention to, rethinking, and readjusting the scale of analysis and the use of digital methods to zoom in and out of various scales of analysis;

- The opportunities and limits of crowdsourcing and opening up the topic of research to subject experts and amateurs outside the university who are willing and interested in participating in the research process;

- The rise of short forms of writing, such as Twitter, and the pressure it generates for both online journalists and academics to produce increasingly brief, easily consumable forms of writing, akin to that of a sound bite, in an environment where there are constant battles for the attention of readers;

- The importance of collaboration, open-source access, and co-authorship; and

- Digital methods as just one tool in our methodological toolkit.

In debating the functionality, effectiveness, and use of digital tools like Twitter it is essential to take into account the bigger picture and how our use of digital tools draws attention to new and different issues and questions, reaches and promotes collaboration among diverse audiences, promotes open-access, and sparks conversation and ideas that may not otherwise arise.

Works Cited

“Getting Started in the Digital Humanities.” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities: Exploring the Digital Humanities 14 Oct 2011. Web. 15 July 2015.

Grandjean, Martin. “[DataViz] The Digital Humanities Network on Twitter (#DH2014).” Martin Grandjean: Digital Humanities | Data Visualization | Network Analysis 14 July 2014. Web. 14 July 2015.

—. “[Twitter Studies] Rewriting History in 140 Characters.” Martin Grandjean: Digital Humanities | Data Visualization | Network Analysis 11 Oct 2014. Web. 14 July 2015.

Koh, Yoree. “Twitter Mulls Expanding Size of Tweets Past 140 Characters.” The Wall Street Journal. 29 Sept 2015. Web.

“Twitter for Research – 1st International & Interdisciplinary Conference, 2015.” Centre for Digital Humanities. 8 Dec 2014. Web. 15 July 2015.